The modern world runs on energy. Petroleum products heat homes and power cars, airplanes and ships. Electricity runs computers and appliances, produces light, and powers an increasing number of cars and a few trains.

Electricity is a “high” form of energy which can be used for almost anything. The least efficient use is to simply route it through a resistive wire to generate heat. It does that very well, but it’s a waste of this high form of energy. As a source of heat, electricity is about as effective as rubbing two sticks together. A lot of energy is consumed to produce a little heat. (Heat pumps are a different story; they’re quite efficient.)

What electricity does more efficiently is to electrify the armature of an electric motor, such as the ones in your washing machine, drier, dishwasher, power tool, air conditioner, garbage disposal and electric car.

When an electric motor armature is electrified, it becomes magnetic – a simple electromagnet. That magnetism engages with the permanent magnets housed in the motor and – voila! – the armature spins. The energy of electricity has been converted into the energy of motion.

That motion gets mechanically translated via gears, chains and whatnot into motion to drive your garbage disposal or automobile or power drill or whatever else you want to produce motion in.

An even better use for electricity is to power computers. Computers are efficient devices. A large portion of the electricity going into them is used productively for their end purpose of computing. Not much is wasted in generating heat or used up in the friction of mechanical gears and chains.

Consider what you get out of your phone, which is powered by a battery weighing less than an old-fashioned D cell flashlight battery. (Remember those?) You’re connected to practically everything in the world, from anywhere in the world. Smart phones are the most amazing invention since the internet, which is the most amazing invention since we invented fire. (OK, we didn’t invent fire, but just invented ways to make it and use it.)

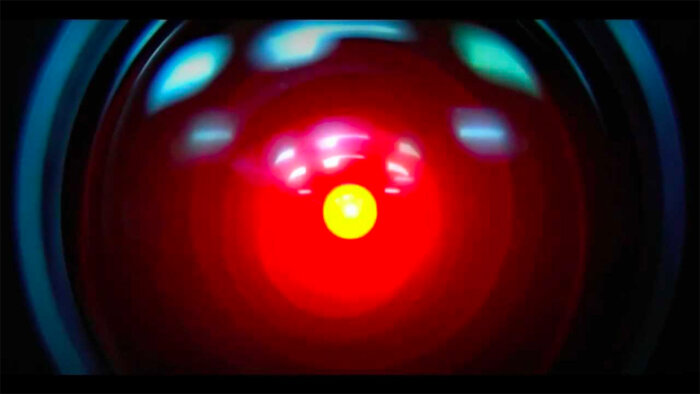

Here’s where artificial intelligence comes in. It’s the most amazing invention since smart phones, and might even surpass smart phones.

“Exponential” is an overused word (typically by people who think it means “big”) but it might be exactly the right word to describe the growth of AI. In the span of a year, we’ve gone from thinking AI might be something like the dot-com investment bubble, or maybe just an old-fashioned scam, to seeing it put hundreds of thousands of people out of work.

And it’s generally accepted that millions more will soon follow. Ironically, AI’s most recent victims include computer programmers. AI now writes computer programs. It even programs itself.

What that means for society is a topic for another column. (Hint: societal wealth will explode, but it won’t be shared equally.)

Today’s topic is how AI solved the electricity shortage.

Yes, there’s an electricity shortage. So-called “renewables” like wind-generated electricity and solar-generated electricity flopped. The cost of wind turbines and solar panels is just too high, they take up too much room, and they’re unreliable.

AI has solved the problem, but not in the way you might assume. Nobody asked AI “how do we solve the electricity crisis?” Even AI lacks the judgment and smarts to answer that question intelligibly.

What happened is this:

AI requires two important things, among others. One is massive, almost incomprehensible monetary investments. The money is used to develop AI, and is used to build humongous AI data processing centers. The monetary investment is AI is already on the magnitude of the inflation-adjusted money spent on the Apollo space program and the interstate highway system – except this time it’s nearly all private money rather than taxpayer money.

These billions of dollars – perhaps trillions now – come from very smart companies headed by very smart people. Think Microsoft, Facebook and Google along with new ones like Nvidia. These aren’t kids in the basement fooling around with “pets.com” and, at least at this stage, they don’t even want or need your money. They have plenty of their own.

The second thing AI requires is related to the first. For those humongous data centers, they need humongous amounts of electricity. Incredible amounts.

You may say that doesn’t solve the electricity shortage. Rather, it makes the shortage even worse.

But making a crisis worse is sometimes the way to solve it.

You see, Big Tech has decided to go nuclear.

Reasonable people have long known that the most effective way to generate energy is through nuclear power. Nuclear reactors produce no greenhouse gasses, uranium is relatively abundant, and the radioactive waste issue is manageable.

But society refused to go nuclear because . . . NUKES!

In fairness, accidents at Three Mile Island, Chernobyl and Fukushima righty gave us pause. But we’ve come a long way, baby, when it comes to safety. Modern nuclear plants are essentially foolproof.

They can also be built on a micro scale. The army recently transported one on an airplane.

The Administration is solidly behind nuclear. Even the Luddite Democrats are largely behind it, even though Trump is too. The reason for this rare agreement is undoubtedly that Big Tech and its Big Money have told both to get behind it.

When Big Tech and Big Money and Big Government all get behind something, Big Things will happen. Nuclear energy is finally coming, in a very big way. The result will be abundant, inexpensive electricity.

That’s a bigger deal than it sounds. It doesn’t just mean that your electric utility bill will be manageable.

Energy is what makes the world go around. The new world will have plenty of it. A good portion of it will be used by AI computers to make society as a whole rich (but unevenly so).