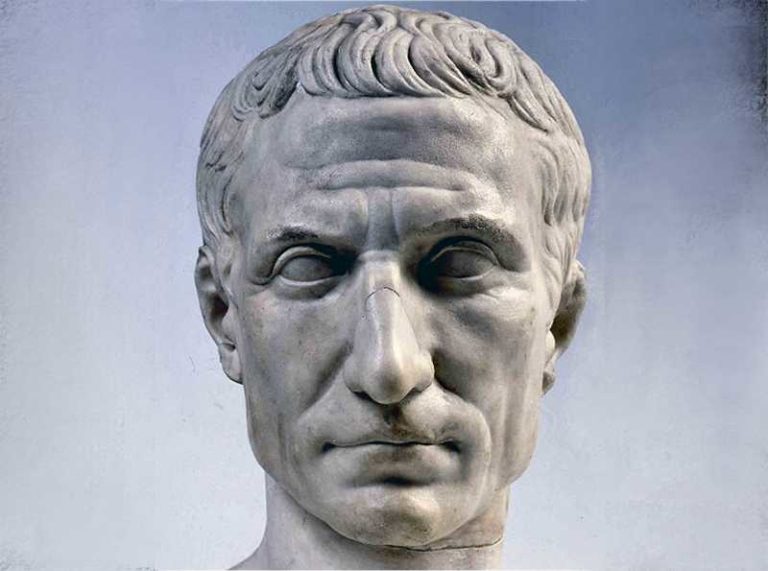

The first to say that was Julius Caesar. After his crushing win over a Persian/Greek king in what is now Turkey, Caesar reported to the Roman Senate with characteristic immodesty and uncharacteristic brevity: “Veni, vidi, vici.”

I came, I saw, I conquered. Caesar had a flair for drama.

He similarly came, saw and conquered most of Gaul – what is now France – in an era well before the invention of B2 stealth bombers. Travelling from Rome to Gaul was an arduous multi-month sea and land adventure. Conquering the barbarians there was a crazy idea for anyone but Caesar.

He laid the foundation for the greatest and longest-lasting empire the world has ever seen. It’s impossible to travel in Europe without marveling at ubiquitous, still-majestic two-thousand-year-old ruins of that empire.

Caesar came from a privileged but not powerful family. Ambitious from the outset, he clawed his way up the political ladder of the Roman republic, a place with a governing structure that we vaguely recognize.

Indeed, we should. Aspects of our own republic consciously imitate Rome, such as the naming of our Senate after the Roman Senatus and even the Greco-Roman architecture of our capital.

Caesar’s foreign exploits were not just to conquer foreign lands. They were to conquer his homeland, Rome. He wanted conquests because he wanted attention because he wanted power – in Rome.

But he also did want to conquer those foreign lands. The Romans were keenly aware of their legendary cousins across the Ionian Sea, and Caesar knew all about the astonishing conquests of Alexander the Great.

When Ceasar was still relatively young (but, he was painfully aware, already older than the age of Alexander when he’d conquered much of the world) he was chosen to be something akin to a prime minister.

Later, during a period of increasing social turmoil in an unwieldy republic deteriorating toward civil war, Caesar was named dictator for life and offered a crown.

He made a show of publicly refusing the crown, but he did not refuse the powers that went with it.

After five years as dictator, at age 56, Caesar was stabbed 23 times by senators. Brutus, too, was one of those senators.

Myth has it that this assassination was because Rome wanted to reclaim its republic from the dictator. The truth is more prosaic – particular senators opposed particular policies of Caesar.

Indeed, the dictatorship, itself, survived and thrived after Caesar’s death. Rome became an empire ruled by a succession of emperors.

That sounds terrible, right?

It wasn’t. It was the best thing that ever happened in the ancient world. For the next centuries, the Pax Romana ensured relative peace, prosperity and enlightenment. There’s a reason that what followed the ultimate crumbling of the Roman Empire is called the Dark Ages and the subsequent period is called the Renaissance or “rebirth” of the civilization that preceded that dark age.

Some Roman emperors were great and good, such as Augustus, Trajan and Hadrian. Rome was at its biggest and best as an empire ruled by emperors, notwithstanding the occasional lunatics like Caligula and Nero. Similarly, Britain achieved the most when it was ruled by kings and queens. Same for Spain and France. There’s a lot to be said for benevolent dictators, so long as they aren’t crazy.

But Americans are taught, or at least used to be taught, that democracy is the ultimate and natural evolution of political governance. Isn’t it wonderful and equitable, say the propagandists, that everyone gets one vote, regardless of what they contribute, what they know, and what they merit?

Isn’t it genius that we rely on ordinary Americans, 50% of whom are stupider than average, to select our leaders?

To ask those questions plainly stated is to answer them. So why have America and other western democracies been so successful?

Arguably, their success is not so much because democracy works well, but despite the fact that it doesn’t. What has worked well instead is something quite different.

It’s technology. The last two hundred years entailed the industrial revolution, the electronics age, and the ongoing computer revolution. Productivity is through the roof, even as people work far less than ever before.

Today’s average westerner is consequently much richer than the kings and queens of yesteryear. He has air conditioning, a house, one or two cars that take him anywhere he wants, only 1.7 children to feed, and a gadget in his pocket to get all the information in the world – and entertainment too – on a magical screen.

It wasn’t democracy that got him all that. It was technology.

If democracy is so great, then why aren’t companies managed by democracies? Shouldn’t we have employees elect their boss by popular vote, just as we elect our political representatives? Shouldn’t there be company-wide referendums by the employees to vote on how hard they have to work and what they get paid for that work?

Again, to ask those questions is to answer them. That system just wouldn’t work. So, what makes us think that such a system works in political governance?

I submit that democracy is not the ultimate evolution of political governance. “One man, one vote,” regardless of merit, does not work over the long run any better now than it did in Athens or Rome – and now we’ve corrupted it still further with universal suffrage and voting by mail.

In the end, this democratic feel-goodery conflicts with meritorious substance. Almost by definition, the meritorious will win that conflict one way or another. Veni, vidi, vici.